After 25 Years, an Artist’s Home Reopens as an Art Gallery

Sea View, conceived by Jorge Pardo as both an artwork and a residence, embraced the dissolution of borders between disciplines.

Matt Stromberg February 5, 2023

LOS ANGELES — In 1993, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles offered Jorge Pardo an exhibition as part of its Focus series. The young Cuban-born artist had begun making a name for himself with objects that blurred the lines between art and design, but this would be his first solo museum show in LA, where he had settled after receiving his BFA from Art Center College of Design in Pasadena in 1988. Instead of creating pieces to display inside a museum, he conceived of an artwork that would exist entirely outside of it. “I have a sloped lot and an idea for a house,” he told Hunter Drohojowska-Philp in the Los Angeles Times in 1998. “How can I take those ingredients and make them do something you wouldn’t expect?”

Five years later, Pardo’s exhibition opened on Sea View Lane, a house conceived as both an artwork and residence perched on a hill in the neighborhood of Mount Washington. Every weekend for the run of the show, shuttle buses would ferry visitors from MOCA’s downtown location to the site in Northeast Los Angeles. “It was an exhibition that could measure what the museum could handle in terms of exercising its domain,” Pardo told Hyperallergic earlier this week. “Where is the object? Is it the house? The artist’s life? The neighborhood?”

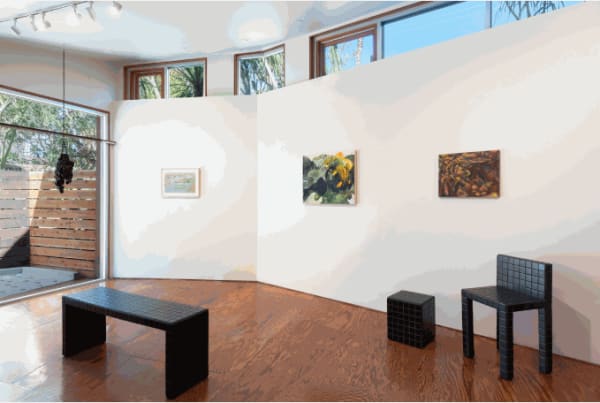

Twenty-five years after the exhibition closed, parts of the house are once again opening their doors to the public — this time as a contemporary art gallery. Last weekend, Sea View opened its inaugural exhibition, River Styx, in a section of the building that formerly housed Pardo’s studio. The project is the brainchild of Sara Lee Hantman, a former senior director at the LA gallery Various Small Fires who also co-founded a furniture company, Prisma, in 2020. Hantman made minimal interventions, adding a few walls for expanded exhibition space but keeping in mind the artist’s original vision.

The gallery’s debut show, curated by Hantman and Brandy Carstens, is named for the path to the underworld in Greek mythology. “It’s about landscape as a ripe place to talk about the psychological environment,” explained Hantman. “The works depict liminal spaces. It’s the antithesis to the pastoral.” These include Kelly Akashi’s ephemeral glass and bronze sculptures; Theodora Allen’s haunting symbolism; Salvo’s spare, abstracted Venetian landscapes; Elsa Munoz’s unnatural, moody seascapes; and Dan Herschlein’s relief paintings whose gnarled surfaces are built up from construction materials.

Pardo’s dissolution of the borders between disciplines made Sea View a compelling gallery location for Hantman. “I’ve always been interested in that grey area between art, design, and architecture,” she said, adding that she views the project as part of the history of LA galleries in homes and domestic spaces that can provide for a more welcoming, leisurely viewing experience than the traditional white cube.

“We have domestic architecture, but we don’t have the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Pardo told the LA Times in 1998. “For me, what formed my understanding of space was experiencing rooms, places, houses.”

Although it was ostensibly a house, Pardo approached the project from an artistic framework as opposed to an architectural one. “He talked about it as a sculpture. He talked about lamps as paintings. Jorge was constantly trying to redefine certain things,” Brian Butler, founder of Pardo’s longtime LA gallery 1301PE, told Hyperallergic.

“I was abusing architecture to some degree, using it like you would a costume for an artwork,” Pardo explained. Pardo has no formal architectural training, and enlisted architect Mark McManus to aid with the technical work on Sea View.

Still, the project does engage with architectural elements and tropes, sliding between continuation and rupture with precedent. Its clean, open aesthetic reflects parallels with the residential modernism of Rudolph Schindler and Frank Lloyd Wright, while its plain, redwood facade links it to other homes nearby. Sea View consists of several linked structures around a central courtyard, responding to the features of the site so that oddly shaped rooms unfold on multiple levels. A staircase doubles as a library and large windows provide light and a connection to the landscape, but disregard the element that gives the street its name.

“What does it mean to not prioritize the sea view on Sea View Lane?” Pardo asks. “Most houses, they build these great rooms with windows to see that little sliver of ocean. I didn’t want to have that money shot.”

When Sea View opened, the exhibition’s curator Ann Goldstein hung Pardo’s lamps in the main space, recalls Butler. “Jorge responded by putting in a circular saw. He wanted to make sure people didn’t think about it as interior space, but as a sculpture.”

When the MOCA exhibition closed in November of 1998, Pardo moved into the house, where he lived with his family for the next 10 years, further complicating the barriers between art, architecture, and domestic space. (The museum reportedly funded $30,000 of the project, while Pardo estimates it cost him $350,000 to finish it.) He would incorporate tiles left over from other projects at Dia Chelsea and the Mountain Bar, a legendary gathering place for artists in Chinatown that Pardo opened in 2003, introducing additional autobiographical layers.

In hindsight, Sea View the gallery could be viewed as the latest chapter of a project that began 30 years ago, undergoing multiple iterations as people collaborate, intervene, and experience the space. “The problems I was interested in were sculptural, spatial issues,” Pardo explained. “How does an installation unfold? When does it fall apart?”

Sea View is open by appointment, Wednesdays through Saturdays.