Erica Mao’s unprotected souls

April 19, 2023 5:20 pm

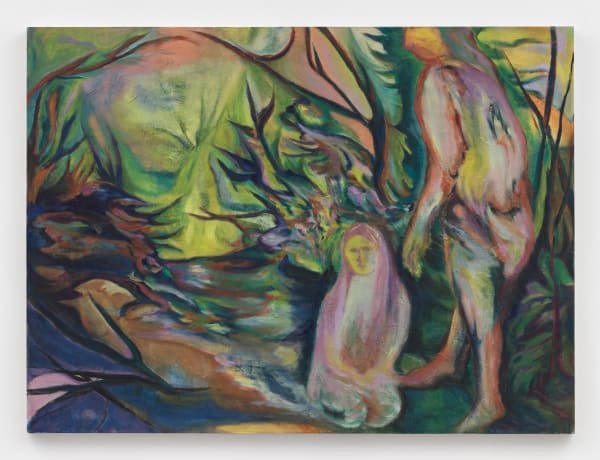

Contributed by Clare Gemima / In Erica Mao’s paintings, presented in “Reach Through the Veil” at Rachel Uffner Gallery, figures flee from danger. Yet the artist does not allow her characters access to refuge, or any guarantee that safety has ever been in reach. Mao has thrashed paint, then re-painted, and then thrashed paint again to create compositions of furious journeying, beating rhythmic anxiety into her characters’ faces. Somewhat cruelly, Mao locks her figures in unwarrantedly self-assured moments, knowingly rendered short by liquified cliffs, exotic swamps, ominous caves, and sulking tree trunks.

Mao paints moments of rest amid vibrating anxiety. In Kneel in the Meadow, the figure with his back to us seems aloof and irritating to his fellow (female) traveler. In the sexier Twin Flames,two melting, fairy-winged figures facing away from each other explode with bright and fiery shades of reds and oranges in a dark, mystical cave. Twin flames are sometimes said to be “mirrored souls” – a connection so powerful it’s best to look away. Although this painting settles on a more manageable psychic balance, it remains unstable and brittle.

Notwithstanding the title of the show, the desperation radiating from Mao’s paintings is a sinister reminder that safety assumed to be within reach is in fact often unreachable. In Flee from the Hunter,a figure appears to be drowning in a river as another that the artist likens to the Greek goddess Artemis approaches her. The plane of the painting is flattened, with minimal differentiation between foreground and background, fixing the figures in a mutual gaze. Mao’s imaginative gestures bolster more than one narrative: the two characters could be cooperative, but they might also be hostile. Caught Through the Reeds likewise captures a shared pause, but a more firmly affectionate and protective one. Two blue figures embrace and prepare for their next move, one attempting to shield the other and reinforcing a confident sense of togetherness, but still against unequivocally foreboding surroundings.

In the gallery’s second room are Mao’s ceramic sculptures, made to recapture certain gestures and brushstrokes through direct touch. Mao herself says she intends to “build houses and sculpt shelters.” Hers are deliberately and explicitly harrowing and unsafe, however, offering little protection. Some, like Orange House, look completely distressed by Mao’s fraught universe. Others, such as Orange Cave, resemble underwater structures, its mother-of-pearl-colored noodles wrapping around a curvy shell. Mountain Atop Table reads as a Stonehenge-esque shelter, indestructible yet vulnerable for any dwellers in its exposure to the elements. Even if Mao’s ceramic enclosures hold out some chance of shelter, they exist only outside her perilous painted world, unavailable to her unsafe and perhaps unsavable drifters. It’s a compellingly sober if discomfiting vision.