Talia Levitt: Schmatta

By Jason Rosenfeld

It has been over two years since I first saw Talia Levitt’s work at ATM Gallery, where the late, lamented Bill Brady introduced me to her striking candy-colored visions that dealt with the female body. Since then, the work has grown larger in scale and scope, and Levitt’s first show at Rachel Uffner is a consistently strong display involving history, visuality, and women’s work. Twelve acrylic on canvas paintings, all but one from 2023, form a kind of faux-embroidered, neo-Divisionist, post-Arts and Crafts Movement, labor-conscious practice. The show is titled Schmatta, Yiddish for old rags or ratty clothes, and hearing it, the classic rock segment of my mind recalls Mick Jagger singing “Shattered” from the Rolling Stones album Some Girls (1978): “All this chitter-chatter, chitter-chatter, chitter-chatter 'bout / Schmatta, schmatta, schmatta, I can't give it away on 7th Avenue / This town's been wearing tatters.” Allegedly written in the back of a New York cab, Jagger’s half-spoken delivery over Keith Richards’s barreling guitar evokes a picaresque masculine survey of Manhattan at the crossroads between disco and punk. The song particularly references the last comprehensive vestige of old New York in Manhattan, 7th Avenue and the Garment District, which will soon give way to the expansion of the newly minted Penn District and the rapacious spread of Hudson Yards luxe. That was the neighborhood where Levitt’s grandmother made military uniforms during World War II, and the labor of fashion is a powerful leitmotif in these pictures.

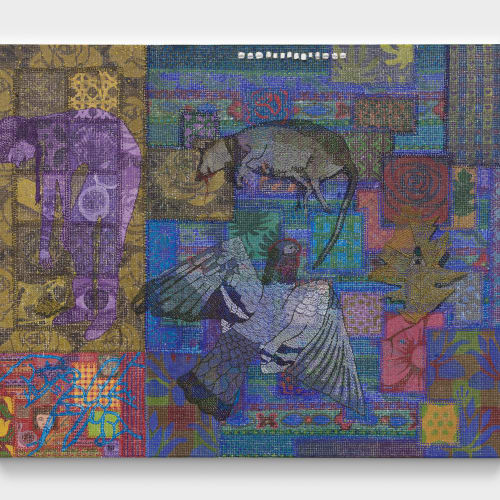

The largest works are six by four or four by six feet. The smallest, NYC Memento Mori (sm), is but 24 by 30 inches. They are all-over compositions with imagery spreading out from the center to the margins. Some, such as the landscape-format Hang-Ups and the portrait-format Painting Day/Night include painted borders, in the mode of Seurat. And this late-nineteenth century French Post-Impressionist Divisionist link is also recalled in the blend of deftly interwoven colors, reminiscent of Ishihara tests wherein numbers are embedded in variously colored dots to measure color blindness. Consequently, Levitt’s paintings reward both close looking and distant perception. Gravity and scale are often suspended in her tableaux, as in the larger NYC Memento Mori, wherein a sewer cover seen from overhead hovers near the upper left above a quilt-like surface of repeated panels featuring skulls, flowers, chevrons, single eyes, and leaves. With its unsteadily drawn circumference, the sewer cover also reads as a kind of large fabric patch; within its center is the famously ambiguous leaf that is the logo for the New York Parks Service, its veining executed using broken lines. Five fallen pigeons are scattered across the composition, in addition to a cigarette case, Greek diner coffee cup, a white plastic bread clip, a surgical mask, broken plastic spoon, and cast blue buttons, all naturalistically rendered—the detritus of daily life.

Although the artist’s mother taught her to sew, none of her works are quilted, sewn, or patched. Levitt instead lays down her compositions in an inimitable technique, first painting the desired overall tones (here orange, pink, yellow, and red) and then laboriously overpainting various details and motifs on top of this layer such that the original colors still can be perceived. Then, using a plastic sandwich bag filled with pigment and with a hole in one corner (seen in a detail in Vanitas Schmatta from 2022), she meticulously pipes in a grid of miniscule, multi-colored lines across the surface—the ultimate refinement of the Impressionist tache married to the Divisionist colored point, connoting a semblance of embroidery. The labor-intensive method, an act of painterly conjuration, results in surfaces that elicit a sense of wonderment, as in the sewer cover in NYC Memento Mori, where this pastry icing method of applying paint with the bag at times results in long, downward trailing lines that read as trompe l’oeil unsnipped threads on the faux-sewn surface.

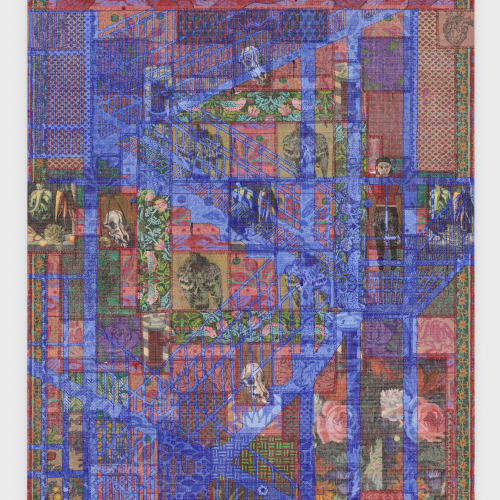

At the bottom of NYC Memento Mori is a row of six panels, each containing a skull. The reference in the title to reminders of mortality casts a historical light on Levitt’s practice, referring to a moralistic still life tradition in art that found its early efflorescence in seventeenth century Spanish art. In fact, a detail of a nature morte by Juan Sanchez Cotán appears in the show-stopping 23-29 Washington Place, Greenwich Village, a New York City sermon in stitched paint. Here, Levitt has Cotán’s carrots and leafy greens share space with a wildly architectonic rendering of a blue interior staircase overlaid upon an unevenly gridded range of designs. These range from animal skulls to snippets of William Morris’s 1883 Strawberry Thief pattern to (more) dead pigeons to a medical diagram of a heart to fire hydrants to refulgent flowers to, at the right, a full-length self-portrait in red top and black pants. All is bordered by a thin edge of looped, red faux-stitched design with a wider register of abstracted flora on a green backing. At the top, on the attic level, is a series of five hand gestures that can only be read as signs of desperation, for the address in the title refers to the site of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911, in which 146 mostly immigrant and mostly female garment workers lost their lives. The factory staircases factored in the tragedy, as management had locked the doors of egress to discourage excessive break times, preventing the trapped workers from getting to safety.

Less desperate hands appear frequently across these pictures, and nicely connect with the idea of both a handmade art and one that salutes the tradition of labor in the schmatta trade in New York. Levitt also mirrors Jagger’s impulse to record one’s immediate urban impressions in the back of a cab in midtown in her practice of titling works such as Drawing on the Train—Day/Night and Drawing on the R. And in Painter Collecting in April, she depicts herself cartoonishly, self-sourcing found material and flora en plein air. Her roving eye and humanist vision that, Whitman-like, collapses citizenry of past and present is best on display in Commuters, in which a collage of female faces from many time periods overlay and underlay images of subway platforms, WPA representations of laborers, and stylized floral decorations. Throughout, the squeezed pattern lines that mimic stitches trace wrinkles, hair, hats, fingers, and eyes. The ragged and the perseverant. A woven community of a century of skilled women, in threads and pigments.