Susan Chen: Purell Night and Day

By MIEKE MARPLE, August 2023

Given the scale of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is surprising to witness a lack of art exhibitions directly addressing this global crisis. The virus dominated the headlines of The New York Times day after day, and Frontline produced numerous documentaries about it, from Trump’s missteps, to our health care system’s fragility, and the communities disproportionately affected by it. Yet, not much about this once-in-a-century event appears explicitly in art exhibitions. That was true at the beginning of the pandemic, and it is especially true now, over three years later, as life returns to a kind of normal.

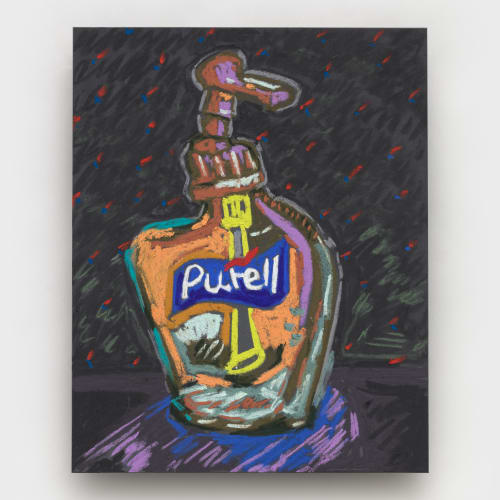

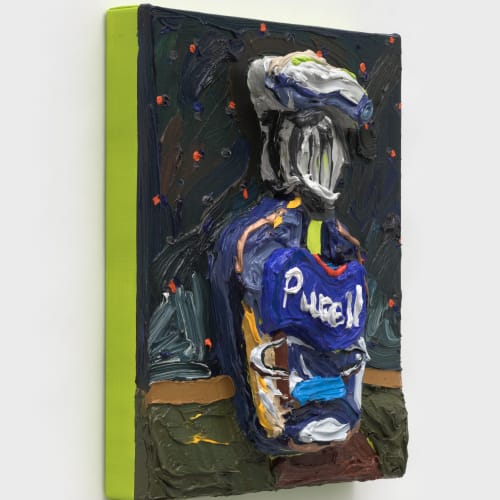

That is what makes Susan Chen’s exhibition “Purell Night and Day” at Rachel Uffner Gallery so refreshing. Her serial studies of Purell bottles with their swooshing utilitarian logos are not only about the pandemic more largely, they are about the period we are in right now. A moment when many have stopped wearing masks and started riding planes again. A moment when people are, once more, shaking hands and hugging friends. A moment when, even as new strains continue to emerge, COVID has stopped being on the forefront of everyone’s mind. An exhale, in other words, after years of breath-holding.

Theoretically, this is when healing begins. It goes without saying that the pandemic was traumatic, even for those who did not lose loved ones. Processing trauma requires emotional bandwidth, which is hard-to-impossible to find in trauma’s midst. Healing is also a slow process. It is a daily and nightly act of taking stock that does not often make for compelling headlines, and continues long after everyone else has moved on.

This is why I loved Chen’s exhibition. It is an invitation to take time: to reflect, to be present, to heal. Time is everywhere in her show, making it the subject as much as Purell or the pandemic. Time is in her installation of two clock faces (one for day and one for night), each made of 12 pastel-drawn Purells. And it is in the differences in color, which indicate different times of day. For instance, the burnt orange outlines in “Purell Clock: Day (#9)” feel like heat waves, suggesting a time closer to midday. While the shadow and blue-to-white gradient of “Purell Clock (Day #7)” intimate a time closer to dawn. The same is true of Chen’s night time bottles, which vary in charcoal patterning and specks of color as the bottles approach midnight.

Chen’s pastel and paint strokes are quick—cartoonish almost. However, they remain safely on the side of sincerity. There is a lightness and levity to her work, though it is far from being “haha” funny. Even her heavily impasto works, in which her bottles literally and figuratively pop, are serious affairs despite their cake-like texture. After all, taking time to reflect—even on a past full of pain and loss—can be sweet and enriching. It has the potential to make a person more open and empathetic, and what is more rewarding, more luscious, than that?

It is not lost on me that Purell is clear. That Chen is painting a see-through substance inside a see-through bottle. Meaning that what she is really drawing when she draws these sanitizers are different qualities of light and atmosphere. This mood-capturing quality makes her bottles a better candidate for talking about the pandemic than, say, N95 masks or BinaxNOW at-home tests because they function almost like mirrors, reflecting the viewer’s emotional state back to them. Purell as emotional yardstick.

If I were to use Purell for my own emotional cataloging, it would look something like this. Before the pandemic, I saw hand sanitizer as a mundane novelty appealing to garden variety hypochondriacs. At the beginning of the pandemic, however, when I was wearing gloves and two masks to the grocery store and wiping down everything I bought, I remember hearing about a man hoarding and selling hand sanitizer and thinking of him as a monster. Two years later, once I’d stopped sanitizing my hands 20 times a day, I saw this same man interviewed for 15 Minutes of Shame, Monica Lewinsky’s documentary about cyberbullying. Through tears, he talked about all the death threats he received for hoarding hand sanitizer. He’d been trying to provide for his family. I felt sorry for never taking his side of the story into account. It helped that I had enough perspective to know that hand sanitizer, or its lack, wasn’t really the cause of so much death. The causes were much darker and more structural than that. Now, I don’t think much about hand sanitizer despite its quiet ubiquity at gas stations, grocery stores, my car console, and everywhere else. And these vignettes are just a small window into the kind of turbulence we’ve collectively weathered as a result of COVID-19.

These important reflections made me wonder why I haven’t seen more art work directly about the pandemic. Or why I, myself, haven’t made any. In the art world, there is a fear of being too on-the-nose. In a Dialogues podcast from 2021 between David Zwirner repped artist Jordan Wolfson and Beeple, the highest selling digital artist, Wolfson told Beeple (who does not shy away from heavy-handedness) that his works reminded him of a New Yorker cartoon. It was not a compliment. The traditional art world tends to prefer art that references current events obliquely. So obliquely, sometimes, that the reference is entirely missed. But why? Isn’t there value in being more direct? In knowing that my thoughts about an artwork are probably going to be similar to yours? Can’t this better facilitate a shared experience, which can better facilitate healing?

Chen’s work still leaves much room for interpretation, but even without reading the press release there is no doubt that these Purell portraits are about the pandemic. Full stop. And I, for one, am grateful for a show that encourages me to take time to remember all that we as individuals, families, towns, countries, and a planet have survived these past three years.

Let’s not be so quick to forget it. WM