In Conversation: Susan Chen

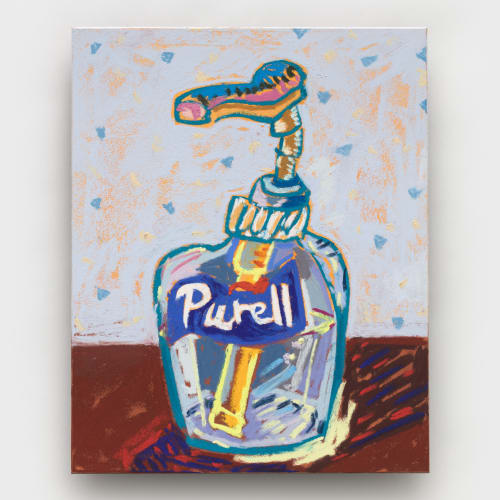

Susan Chen’s “Purell Night & Day” casts the humble hand sanitizer in an entirely new light

Sky O'Brien

August 13, 2023

Susan Chen (b. 1992, Hong Kong SAR, China) is a New York-based artist who has used oil paint and other materials to reimagine the representation of communities from the Asian diaspora in thickly painted and boldly colored figurative portraits. Her current exhibition “Purell Night & Day,” which runs until August 18, 2023 at Rachel Uffner Gallery in New York, takes the concept of purification in a time of tragedy, as symbolized by the Purell bottle, to its limit. We spoke in July and our conversation was condensed and edited for clarity.

SKY O’BRIEN: How did you come up with the idea to paint bottles of Purell hand sanitizer?

SUSAN CHEN: I don’t know about you, but I see Purell everywhere—in restaurants, schools, and shops. It’s this little figure, a bit ghostlike, that’s just lurking around in the background now. I thought about how this “99.99%” stuff is supposed to mass disinfect humanity and the entire world. I remember getting on a plane and they were dishing out Purell wipes to everyone. It was a 300-person-full flight, and I thought there was something peculiar about it. Like, Oh, you’re all going to squish in this small condensed space for 4 hours and these wipes are going to stop you from getting a disease from the person next door.

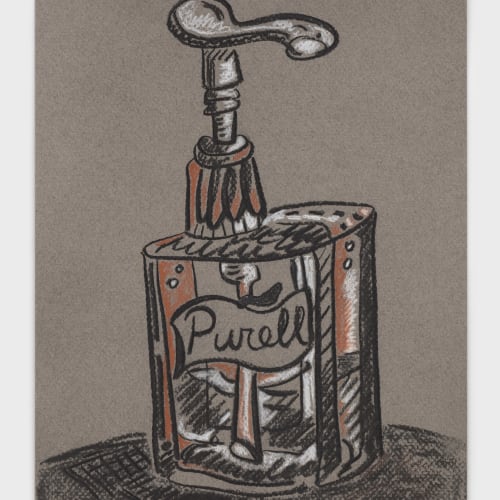

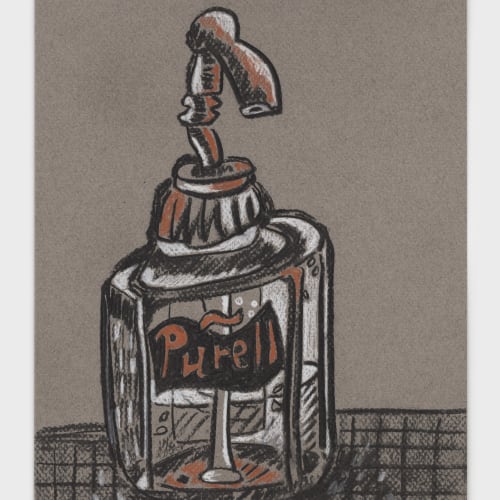

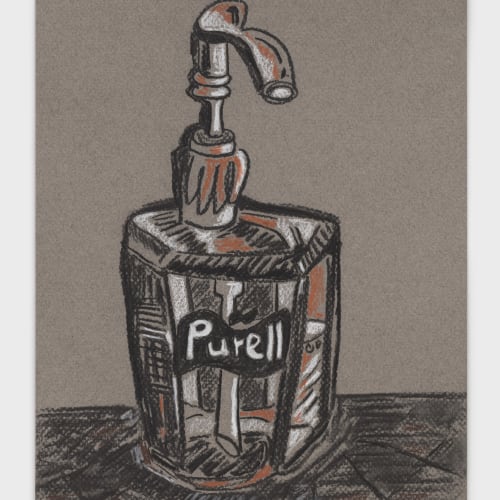

I picked Purell because it seemed like the most popular brand of hand sanitizer—Purell and hand sanitizer are kind of interchangeable. When I started doing the pastels, I was actually nervous—if I didn’t put in the Purell words, would people read them as Purell? I realized that they could be read as soap bottles or something else.

The last global pandemic happened 100 years ago, but I’ve personally lived through SARS in 2005 and Swine in 2009. The coronavirus felt like a third version to me, on a grander scale. SARS and Swine killed a lot of people, but in the aftermath I witnessed how everyone seemed to forget the period. For example, there were no policy changes in the controlling of wet markets. Society moved on quickly. Covid is obviously on a grander scale, and I wonder if we will similarly forget it in a few years time. But for now, this hand sanitizer is like a ghost lurking in the background.

Did these feelings shape your color choices and composition? Your Purells are not representational.

That’s more of an artist’s challenge. It’s easy to paint something realistic, the challenge is always, how do you paint something abstract or different? And how do you paint the same thing in a hundred different ways? I did a version of the clock where each hour was a different color and it just didn’t look right. Something I learned from the show is how to limit my color palette. Less is more—and maybe writers have this too, as a challenge of growth. As a painter, I’m always trying to ask, How can I say the most with the least amount? Sometimes I think of Matisse’s cutouts at the end of his life—you know, they’re very simple, but they get to the point. For a painter to grow in the long run, I wonder, how do you edit things out?

There’s one piece in the show, Purell Tower, 2023, that’s more figurative and almost surreal, where hordes of sanitizer bottles make up a person’s body. You’ve made a few self portraits in your career and I was wondering if this is another self portrait.

It could definitely be a self portrait, but I purposefully shaped the canvas into the size of a full length mirror. So there’s an element of reflection. And I wanted it to be a tower. At first, I wanted to make a really, really big painting, but I only had two months to put the show together—you know, when the gallery shows up in March, and it’s like, could you take this slot in June. So I asked myself, What can I do in two months? It was good because it put me under pressure. I thought, this is a summer show, and summer’s about experimenting. This is a good time to try a bunch of different things and if it fails, it’s summer, no one will really see it.

Purell Tower is related to Covid, but also metaphorically it could represent any woman. Sometimes society puts greater pressure on women to seek perfection or a higher standard of cleanliness. Even just hours spent on domestic cleaning. I think Bill and Melinda Gates did a study and found that on average women do seven extra years of domestic work than men—in that time, you could get a PhD! Looking back at previous paintings, this theme seems to pop up here and there. I’m always fascinated by cleaning products and how they’re related to being a woman. Like why are the two inextricably tied to one another? We’re lucky we live in a more progressive country, but in other parts of the world, the two are very much intertwined.

Did the way you look at Purell change over the course of those two months?

At the beginning, I was amazed that this tiny bottle could hold an entire world’s sense of disaster and paranoia and grief—and it all fits in the size of your hand. This thing carries a lot of weight for its size. I painted three Purells every day for two months. I did feel like I was going a little crazy by the end. But did I see a change? I’m not sure. I was curious to discover that Purell is a third generation and now female-owned brand. This idea of branding capitalism and the question of who wins during a war was something that crossed my mind. During Hurricane Sandy, all these roof shingle companies were like, Oh, it would be great to have more storms so that we can sell more roof shingles. During a pandemic, so many people are losers, but who are the possible winners?

Painting these things every day, there was also an element of hoarding that is very reflective of what was happening during Covid. I also did clocks because I wanted to cast a time marker, whether it’s the time marker of the end of a journey or just a time marker of an element of stillness that was in everyone’s lives for a period. There was also this idea of night and day. I didn’t realize that “night and day” was an English idiom that meant things were getting better.

Will you talk about the arrangement of Purell Clock: Day and Purell Clock: Night?

Originally, I wanted to do a clock where I was reflecting the different hours of the day and capturing the time of day. However, I quickly realized this was very hard technically. Also, 1:00 PM and 1:00 AM are different. So I turned it into a night and day clock. The clock is a symbol of something ongoing, you know, like 24 hours of disinfecting that’s happening around the world. I don’t know, there’s something uncanny about the mass disinfecting of society. The idea that this is going to fix all of us, like a universal savior. There’s some dark humor there.

When I look at these paintings, I’m reminded of Andy Warhol’s soup cans and Wayne Thiebaud’s cakes. Did Pop Art shape how you painted and drew this series?

Oh, absolutely. Warhol’s soup cans were very much about American consumerism, commercialism, branding, and entering into the age of advertising, like in Mad Men. And Wayne Thiebaud is very much about looking—just looking at things—and capturing color at different hours of the day under California light. I haven’t seen his pastels in real life, but I know he’s made them, and I know he’s had pastel shows in the past. Of course, we always think about Morandi when we think of still life. It’s funny because Morandi was painting these vases and bottles back then, but in contemporary art today, it’s like the Purell bottle is a replacement for these simple ceramic structures.

I got into pastels because I saw a Paula Rego retrospective for the first time last year. Her work blew my mind. I realized that the majority of her works are pastels mounted on aluminum panels. That’s how I got into soft pastel. But I didn’t know I was allergic to them. I started using these soft pastels and I was like, Why do my lungs feel like they’re on fire? I had to take an allergy test for something else that happened around the same time and turns out I’m really allergic to pastels. I had to wear a PPE bubble helmet the whole time I made those works. There’s some sort of irony that I was painting Purell bottles in PPE. But I guess it didn’t stop me.

I was also thinking of Sam Messer’s series of typewriters that are really beautifully painted in oils. And Chris Ofili had this watercolor practice where every morning he’d spend 30 minutes drawing a little head on paper. I like the idea of joining a lineage of artists who were making work by looking at something really mundane and amplifying it. I don’t know if anyone else has looked so closely at sanitizer.

Sanitizer is such a modern invention, and you’re creating a new way of looking at it in the context of the pandemic. You also used foam as a material in this series, is that right?

There are two or three paintings in the show with foam. In my studio I went down this rabbit hole of impasto painting and ways of building up surfaces and making paints thicker. I thought I would experiment by cutting out foam and preparing the surface with acrylic and oil ground and then painting on top of that. I thought this would allow me to make some interesting paintings on a larger scale. But cutting foam is pretty tedious. Either you have to cut it with a hot wire cutter—this is insulation foam used in homes—or you’re using sculpting foam and that also creates a lot of toxic dust. It didn’t leave me as satisfied as I thought it would. It almost felt like a gimmick. Maybe I just didn’t enjoy putting that surface together. Epoxy is hardcore.

So you wouldn’t use it again?

Using foam for small paintings is doable. But for large paintings it would definitely take more than one person to try to build the surface, or just a long time.

You entered the art world at the start of the pandemic, and a lot of your work has responded to the way the pandemic has shaped culture in the United States. What’s next?

I recently moved into a commercial studio space that is not in a school setting or in a home garage or artist residency. I’m working on my next show due in March and it’s mostly themed around women’s advocacy. It feels easy and there’s a kinship to working with women, especially during a time when abortion laws have changed. It’s been really reassuring to have different women come through the studio to share their personal stories, and that collectively we are creating an exhibition together.

I think I make work in response to real time: what’s happening around me and what I see in the news. I don’t think all artists work this way, that is, reacting so directly to the news, and sometimes there is a lag time between what I see happening in society and then getting it down on paper. I equate my job sometimes to feeling like a journalist. I’m often amazed by market-successful artists who can keep painting the same subject matter for 5-10 years.

Coming out of graduate school, I am adjusting to what it means to be an artist working in the market. I feel like I came into this sort of naively. It’s easier to make art when you don’t have market pressure and can make whatever you want to make. Part of making these Purells again and again and again might be subconsciously related to being like, Oh my God, I actually have to pay studio rent. I have to be able to afford rent this month. And so my hours of being able to generate something completely new gets cut short.

This is something I’m trying to get used to. Suddenly, I understand why someone would make the same work for 10 years. Sometimes you just have to pay for things, you know—like your life and kids and studio rent and stuff like that, your priorities also shift at different stages in your life. And sometimes collectors just want oil paintings (auction-friendly works), or collect “what you are known for,” and there can be little room for experimentation when you need to cover real life expenses.

It really changes my idea of what it means to be a successful artist. I’m trying my best to keep making work with intention at the core of my studio practice, but I can see how this gets difficult, and you really have to protect it.